Morbid symptoms of parliamentary decay

As our societies in the West fracture, it becomes increasingly difficult to keep the ship of state afloat. That sinking feeling grows ever stronger.

Discussing the Ukraine conflict and the drone attack on the Kremlin on his blog “Indian Punchline” last month, retired diplomat M. K. Bhadrakumar observed how profoundly Europe has lost its way (emphasis mine):

This will probably show up in history books as a historic failure of European leadership and at its core lies the paradox that it is not France but the German government that has aligned itself closer with the US in the Ukraine war and risking an intra-European “epoch of confrontation.”

Even otherwise, these are fateful times, with the political middle ground already shrinking in France and Italy and is much weakened in Germany itself in the wake of the pandemic, the war, and inflation. Importantly, this is only partly an economic story, as the decline of the centre and the de-industrialisation in Europe are closely related and the social fabric that supported the centre has come unstuck.

Germany, the powerhouse of Europe, has been relatively lucky so far. It benefited from cheap labour from east Europe and cheap gas from Russia. But that is over now and the decline of German industry is foreseeable. When society fragments, the political system also fragments and it will take progressively greater effort to govern such countries. Germany and Italy have a three-party coalitions; the Netherlands has four parties; Belgium has a seven-party coalition.

(“Zelensky regime’s fate is sealed”, 4 May 2023)

In this post, I would like to look more closely at the process of fragmentation that he refers to above. In Europe's parliamentary systems, where parties rarely to get absolute majorities, shifting multi-party alliances are the rule. So what's behind the instability today? What's making our governance systems so fragile?

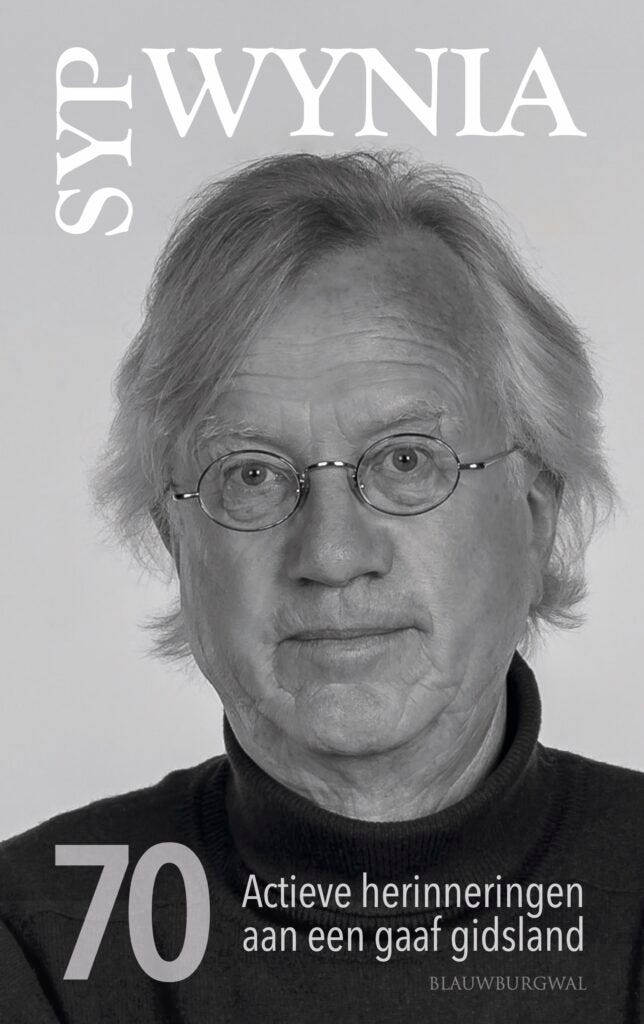

To offer some insight into how this works in here in Holland, which in our case is ruled by a coalition of only four parties (poor Belgium!), I turn once again to the independent Dutch commentator Syp Wynia, who I have cited previously in these pages.

Wynia recently published a commentary, “In Nederland wordt al tien jaar niet naar de kiezer geluisterd” (For the past ten years the voters have been ignored), in which he unpacked for us how the increasingly dysfunctional coalition-forming process works in practice. From his excellent site, Wynia’s Week (my translation):

There is hardly any relationship between the elections and what happens afterwards,. At 9 p.m. the ballot boxes close and what happens after that is a black box. That box remains closed for months, without the citizens having the slightest idea of what goes on inside. It also takes longer and longer before that box is opened. Last time it took nine months. You can't say what cabinet plans emerged then was a result of the elections.

This has become a pattern, especially during the Rutte years: formations take longer and longer, the voter gets further and further out of the picture, and what plans are put together in the formation is not recognizable as a follow-up to the election debates or as a response to citizens' concerns. The cabinet formation takes place in its own bubble in The Hague, which has become detached from the country.

While plans for the Netherlands are made in this bubble in The Hague without citizens — and also most of the people's representatives — having any idea about it, there are privileged interest groups that do have access to the formation discussions. This can involve both 'right-wing' interests — large corporations — and 'left-wing' interests: pressure groups for nature, climate, the environment, slavery [acknowledgement of injustices of the colonial past, ed.], development aid, 'gender', asylum seekers and trade unions. Those do get their due. Whether the same goes for the country's citizens remains very much to be seen.

In other words, the process is largely if not entirely driven by lobbyists working behind the scenes. One might endorse a given lobby, such a trade union or a environmental group, and thus favor the outcome, but the entire process remains opaque and highly arbitrary. What results from the “sausage-making” has at best only passing resemblance to a public mandate.

Worse, the so-called coalition agreement (coalitieakkoord) that results has in recent years become increasingly lengthy, specific, and even contradictory. This comes about the because the leading party (in our case the center-right VVD) needs three other parties to obtain a majority and hence an enormous amount of wheeling and dealing takes place behind the scenes to come to some kind of agreement. This produces an inherently fragile system, reflecting the ever-deepening fragmentation.

To keep this delicate arrangement in place, the governing parties rigidly adhere to the coalition agreement; it becomes in effect binding. This gives the parliamentary debates a certain ritualistic character. It isn’t for the lack of opposition; you do hear opposition parliamentarians (several of whom are outstanding) making at times eloquent appeals. But time and time again, the governing coalition votes in bloc, and this applies not only within the coalition but within the parties themselves; “kadaverdiscipline” is strictly maintained, party members who dare to deviate from the “party line” are sanctioned..

Calls are increasingly heard for the abandonment of this rigid adherence to governing accords, that it gravely undermines the ability for parliament to exercise its supervisory capacity, but the system remains intact. Perhaps the most prominent critic of the current system is eminence gris of the Dutch Labour Party (PvdA), Herman Tjeenk Willink, who has served as informateur and seen the coalition forming process first-hand:

Restoring the right balance of power and counter-power "requires a different kind of coalition agreement," Tjeenk Willink said. ''We cannot do it the old way and then just preach more dualism. A buttoned-up coalition agreement puts the opposition on the sidelines and hinders counter-power."

“Tjeenk Willink gooit het roer om: dunner regeerakkoord, niet praten over poppetjes”, AD, 7 April 2021)

The process is now reading a nadir of dysfunction; the four governing parties sharing power are seeing their approval ratings plummet in polls. Long overdue, real, broad-based opposition is emerging, so that means tip-toeing through the tulips to keep the faltering enterprise alive. A collapse would mean fresh elections, and they know that may very well finally seal their political fate, as regime change finally comes to The Hague.

If you live in a parliamentary system in circumstances similar to those of the Netherlands, which, as M. K. Bhadrakumar observes, is the case in most Western European countries, you will probably see something that resembles this. Naturally the process, the issues, and the outcomes may be different but the general contours should be recognizable.

There is however one additional factor at play which is specific to Holland. As I detailed last year, Mark Rutte is now the long-serving prime minister in the postwar era. Currently leading his fourth coalition, referred to as Rutte VI, he has proven to be a master at manipulating the coalition-forming process to serve his ends, which, as always, to gain and remain in power, whatever the cost. In the beginning of 2021 his third coalition, Rutte III, collapsed due to devastating critique of childcare support scandal, casting him in a very bad light indeed, with much criticism, including from his coalition partners. The sense of desperation for meaningful change in leadership and direction was palpable, yet after the subsequent elections and an agonizingly long coalition forming process (no less than nine months this time around), Mark Rutte rose like a phoenix from the ashes with his forth coalition, the exactly same partners (apparently they must have collectively held their noses), back to business as usual. Plus ça change, plus c'est la même chose never seemed more apt.

Last week, apropos a parliamentary inquiry the Groningen gas crisis (the earthquake damage) that was scathingly critical (vernietigend) of the governments actions (or rather, lack thereof), parliamentary hearings were held during which we saw the passionate, emotional appeal of a parliamentarian from Groningen, Sandra Beckerman (Socialist Party), who has been campaigning tirelessly since entering in the Lower House in 2017 to see that the Groningers are adequately compensated in a timely way for their broken homes and broken lives. She bitterly reminded Rutte of his past promises to “do the right thing” for her constituency, his abject failure to live up to his word and take action to break though the ghastly and inhuman bureaucratic logjams detailed in the parliamentary report that produce the institutional cruelty so characteristic of the neoliberal age.

During her impassioned reproach, one sees Rutte sitting stony-faced, shuffling some papers, reading text messages on his phone, eventually responding in the form of perfunctory, desultory comments, how he “didn't realize the seriousness of the situation until 2018”. He says what he needs to say, but he exhibits a narcissism, a lack of empathy, a profound indifference to genuine public sentiment that precludes a meaningful response to this and other scandals and crises which continue to fester. He clings fervently to power in The Hague, but is incapable offering real leadership. “To govern is to chose”, but Rutte can not, will not make hard choices.

‘To govern is to choose’. It was Pierre Mendes-France’s maxim when Premier of France in 1954-5, cutting through the morass of postponed decisions left by weak coalition governments and negotiating the withdrawal of French troops form Indo-China. Good government means taking decisions, even when they are hard decisions.

I see it as a delay of unavoidable realization of full servitude to empire, maybe people will start protesting as they did during WW2 and bring a people's driven power back..... it is possible, it is only a matter of people figuring it out.