That 'Dutch disease' persists

Another long-festering crisis in the Netherlands has recently came to head. It concerns compensation for the impact of extracting natural gas in the northern province of Groningen.

Massive natural gas reserves were discovered in the Dutch province of Groningen in the late 1950s. The opening paragraphs of the Wikipedia article offer a useful summary:

The Groningen gas field is a natural gas field in Groningen province in the northeastern part of the Netherlands. With an estimated 2,740 billion cubic metres of recoverable natural gas it is the largest natural gas field in Europe and one of the largest in the world. The gas field was discovered in 1959 near Slochteren. The subsequent extraction of the natural gas became central to the energy supply in the Netherlands. Virtually all of the Netherlands was connected to Groningen gas in the following years. Revenue from natural gas production became important in the post-war development and construction of the Dutch welfare state.

As of 2013, 2,057 billion cubic metres of natural gas had been extracted from the field.[2] Gas extraction resulted in subsidence above the field. From 1991 this was also accompanied by earthquakes. This led to damage to houses and unrest among residents. It was decided to phase out gas extraction from 2014 onwards. The Groningen gas field is expected to be closed between 2025 and 2028, with the possibility of bringing this forward. The reinforcement operation and damage settlement as a result of the earthquakes are progressing slowly. The National Ombudsman called this a "national crisis" in 2021.

A parliamentary inquiry was launched in 2021 to investigate the situation. In late February it shared its findings. As described in the NRC, a liberal, mainstream newspaper, the picture that has emerged is of “the almost total inability, sometimes bordering on unwillingness” of the Dutch government to correct course:

The committee describes a public administration that is completely inward-looking, convinced of its own rightness, deaf to signals from outside and to warnings from its own regulator. The government is responsible for an "unprecedented systemic failure" — along with the gas and oil companies Shell and Exxon [through their joint venture NAM]. The actions of the companies are also regularly "shocking," "outrageous" or "particularly culpable," according to the committee. But it is ultimately the government that has failed to stand up for the public interest.

(Derk Stokmans: “Het bewust wegkijken van de problemen in Groningen is symbolisch voor het tijdperk-Rutte”, NRC, 24 February 2023)

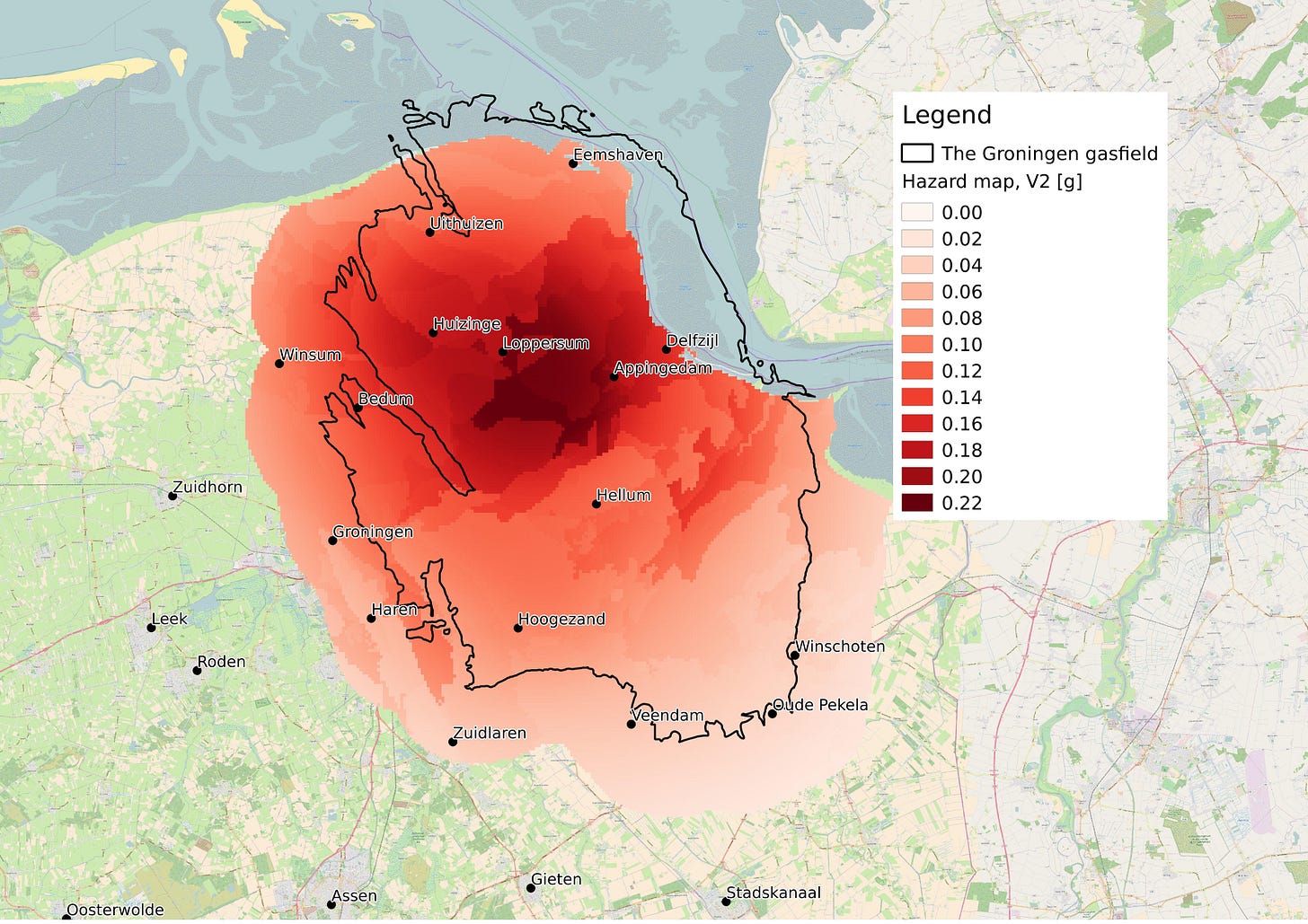

Tens of thousands buildings have been damaged or otherwise affected by the recurring earthquakes. The most affected area is land reclaimed in earlier centuries from what was once vast peat bogs and tidal wetlands. Further inland in the province, the sandier ground is firmer and the buildings less affected.

One particular parliamentarian from Groningen, Sandra Beckerman (Dutch Socialist Party) has been tirelessly working to turn the spotlight on the topic and I’ve read some of the research that she has done among those who have been affected. It makes for harrowing reading. She has compiled countless stories of how homeowners, farmers, small businesses and the like, are nickle and dimed to death by an indifferent if not actively hostile bureaucracy. Follow The Money, a Dutch investigative journalism collective, has been for some years now compiling a Groningen Gas dossier; back in 2018 one contributor, Sam Gerrits, a geochemist, cited a 2015 estimate that properly stabilizing and reinforcing the estimated 150,000 buildings at risk to earthquakes would cost an estimated €25 billion, money neither that the government has reserved nor the energy companies want to spend. Instead, the repairs are grudgingly paid for; no effort is made to truly compensate the Groningers in a just and adequate way. Many are stuck in homes and farmhouses they can neither afford to repair nor are able to sell.

The inevitable geological impact of gas extraction was wholly predictable, and in fact was predicted. W.A.B. Meiborg, a renowned civil engineer from Groningen, published in 1963 his estimate that the province would experience subsidence of around a meter. Although he didn’t explicitly anticipate earthquakes, he nonetheless warned that the consequences would be serious and that “substantial financial reserves” should be set aside to deal in the future with the problem. The Nederlandse Aardolie Maatschappij (NAM), the joint venture established to exploit the country’s energy reserves by Shell and Exxon (the Dutch state is also a shareholder) calculated at the time that subsidence could in fact reach a meter and a half. However, it suppressed these findings and chose instead to shoot the messenger; they smeared the reputation of Meiborg, “cancelling him” as we would say these days. Given the euphoria of the moment, no one wanted to contemplate any potential downside to the discovery of this wondrous bounty of fossil fuel wealth. Meiborg was subsequently vindicated, but only after his death in 1967.

The Dutch government chose not to establish a financial reserve in the form of a sovereign wealth fund or something similar, but instead used the vast revenues (a whopping €363 billion to date, according to the NRC) to fund social welfare programs and several major (and important) infrastructure projects, such as the Delta Works, the massive coastal flood control system which I wrote about earlier. Whatever one thinks of those decisions, it is alas the Groningers who have been paying the price.

By the way, the term “Dutch disease”, which I refer to in the title, was coined by economists because of what happened here; it alludes to how the discovery and rapid exploitation of such a windfall can skewer the exchange rate of a country’s currency and damage its economic competitiveness. The compensation crisis reveals yet another malignant symptom.

The first earthquake was detected in 1976. The NAM denied that it was related to gas extraction. However, the 2012 Huizinge earthquake, which measured 3.6 on the Richter scale, caused widespread damage and finally the link to the gas extraction activities became undeniable. Only some ten percent of the original reserves now remain and by way of throwing a bone to the affected province (and perhaps placate the idealistic Greens as well) the government announced plans several years ago to wind down gas extraction by 2030, at which point the fields would be basically empty anyway. Unfortunately, is it a real possibility that earthquakes will continue to plague the area as the ground continues to subside in the coming decades.

One shocking but wholly unsurprising dimension to this lingering, festering crisis is that is remarkably similar to the Childcare benefits scandal, which simmered for years before coming to a head at the end of 2020, bringing down Mark Rutte’s third coalition government, precipitating early elections. (Despite wide dismay and discontent about the affair, “Teflon Mark” and his party, the VVD, managed to emerge unscathed, more or less, to lead a fourth coalition in the fall of 2021.) Rutte expressed his personal anguish at the findings of the parliamentary inquiry into the situation in Groningen, but asked the Groningers “for their understanding”, which appears to be the way this narcissistic leader tries to express empathy (“we are victims of the situation too”). Apropos of the childcare benefits scandal, Rutte promised “better governance”, but there has been scant sign of that, nor is any meaningful change likely in the case of Groningen. Within their insular bubble in the Hague, these things simply don’t matter to the current governing class. There is yet no coherent opposition, and Mark Rutte’s fragile ruling coalition continues to draw on the tacit support of the country’s large and exceedingly complacent cosmopolitan professional-managerial class, for whom real-world activities such as fossil fuel extraction and industrial farming are “icky” matters not on their radars. Out of sight, out of mind.

Holland remains for many of us still a very functional society; despite the broken system of national governance this is undeniably so. The problem is for those who, even for no fault of their own, fall through the cracks; it then becomes a nightmare, a banana republic if you will. When I was in the province of Friesland last summer, I saw the protest flag pictured below. I shared the photo below previously, and do so now again.

The PMCs live in a delusional bubble. And they've gone to cult-like extremes to make sure nothing can penetrate the bubble's narrative maintenance—especially those icky things. I'd love to figure to provide them with effective exit-counselling.

Small earthquakes and minor housing damage do not make a crisis. If you visit Groningen and talk to the people there they will tell you so.

The gas crisis is PMC propaganda to shut down domestic gas production. (Production for international customers continues.) It implements the desire to increase energy prices and to switch consumers from gas to electricity. There may be good reasons to do so, it's hard to tell with motivation.